The Unseen and Present in the Fold series of Adler Guerrier by Joey Chin

What comes to mind when we think of the built environment outside of urban planning and real estate development—macro concepts and visions of master plans for land use or precinct rejuvenation?

Looking at the Fold series, an ongoing project from 2015 by Miami-based artist Adler Guerrier, I thought of the built environment as a concept that can be contemplated about as being closer to home, in the literal and metaphorical sense.

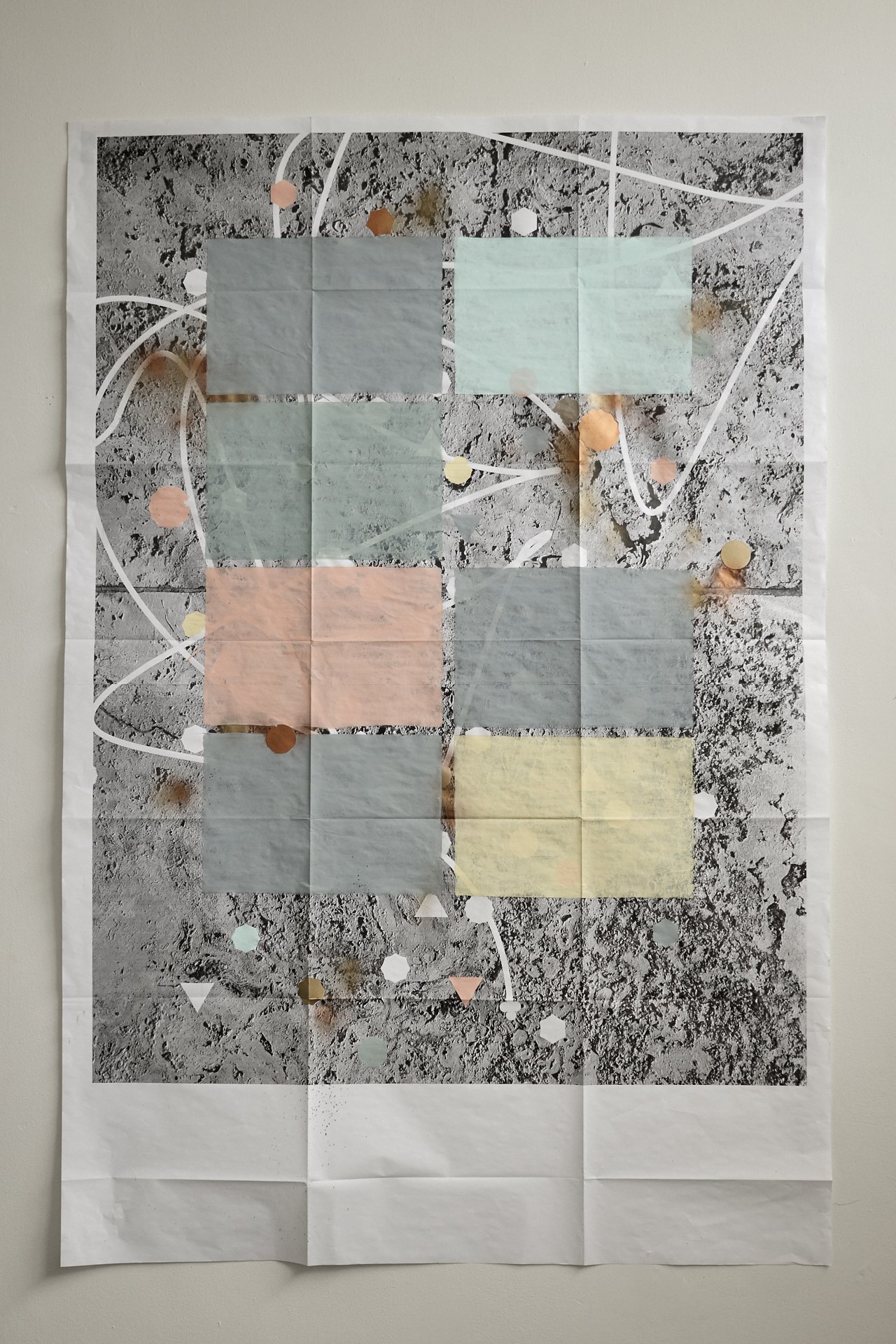

In various backgrounds of each artwork with the banner name of Untitled, there is a photographic image of flowers, branches or leaves in black and white.

Even as I view the artworks through the filter of a computer screen, the details are unmistakable; close enough to discern the fingers and spikes of fronds, the waxy gleaming of leaves, the filament of branches.

In a conversation I had with the artist, he mentioned that the background image was, in fact, of a hedge. He was driving, and happened to have his camera in the car when he chanced upon this particular hedge, an outdoor setting of plants partially shielding the backyard and the home that it surrounds.

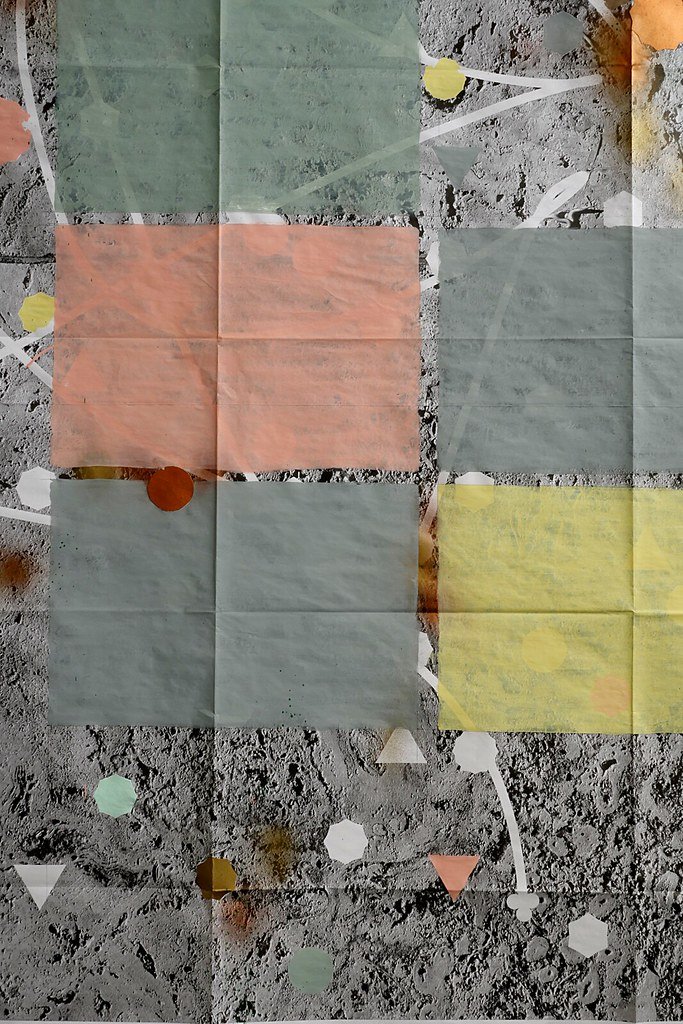

I am drawn to the details of botany in the background whilst distributing my attention to other icons: colourful geometric shapes and sizes of hexagons, triangles and diamonds painted in a soothing palette of earthy hues, cool pastels, and glinting in burnt gold and orange-bronze. Some are free, and others strung through white precise curves and lines.

Yet, the most distinctive shapes of all are the painted rectangles that front the pieces.

Opaque and bold, they restrict access, almost with the statement of a censor, to a fuller image of the hedge in the background for the viewer.

Unlike hedges in real life that exist in the fringe and foreground to discourage interactions between the private individual and the public other, the images in the artworks from the hedge reside in the back.

A triangulation of ownership, visibility and space from the visual indices's brought me to the thoughts of spatial conditions of how we desire, maintain, or respond to privacy through the built environment.

I am pulled to the inversion, this shuffling of positions of the plants and shapes in between background and foreground, the paradox of being unseen and present, obstructed and observed at the same time.

Almost a visual erasure and omission, I consider the shifting irony in power: the adaptations made for blocking is now blocked.

If I find myself being overly occupied with what appears to be strategically painted shapes, their obstruction to the photograph in the background reminiscent of privacy solutions and keeping out of sight, it must have something to do with where I live, in space-scarce Singapore.

Like 80% of the population, I reside in public housing that usually takes the form of towering apartment blocks. With the exception of two corner flats on the left and right end of a story, everyone else lives in what is referred to as a “corridor unit”.

If the door is open, it is possible to see right into another resident’s home; their living room; domestic activity and their furniture layout when a neighbour walks past the corridor area to return to their own unit.

Privacy is negotiated typically in the form of sheer or opaque, drawn or shut curtains and windows, an open or closed door and blinds.

Unlike the fixed or semi-fixed structure of a wall or hedge to block out wandering eyes erected in places where land is less competitive, the choreography and negotiation of privacy in Singapore flats are more flexible and less permanent.

Yet, when I return to the comparison of landscaping solutions of a hedge, and the rectangular visual metaphors in the Fold series for keeping out of view, I think that regardless of permanent or flexible adaptations, of people and places, ultimately, the very desire to be out of sight is one that is imperative.

And yet it is to simultaneously declare “here I am”, like the surfaces of painted colours recurring across the photographs.

I told Guerrier that they remind me of the function of large-scale decals covering the exterior of a soon-to-be opened shop.

Usually to hide the interior undergoing the renovation process, these decals also announce to passersby the promise of something new through its impending presence, whilst severing the previous identity, or establishing a renewed identity, of what used to stand before this.

Hence, the allusions of identity, through belonging and territory within spatial configurations are sometimes difficult to extricate from the implications of privacy, much like the blocks and shapes arranged in the artworks.

Apart from the painted ones, there are other rectangles that are congruent in the series: as a result of paper being folded.

There are lines that march through each piece in their exhibition. Almost a demand or command in concealment—like the lines made, not necessarily only from drawing, but marking and folding—and also, silent surveillance.

Privacy, though entails navigating out of sight-lines and reticence, does not eliminate observance and individuality. The shapes state their statement.

The notion of an inner life, an interiority that exists even if its presence is not obvious, extends to one of the pieces, Untitled (Place marked with an impulse, found to be held within the fold) ii and Untitled (held within the fold; marks, trace) ii.

Folded to the size of 22 by 16 inches, they considerably smaller than the others. As though their closed bodies are indexical of hiding something, I find myself contemplating the bigger image if opened: if the white lines that circle the surface might actually meet at some point within the folds, what the larger border would look like, if there might be rectangles beneath.

From which coordinates does the image begin? Surely what we see cannot be all there is. Apart from what exists in(side) paper, I ponder also about text and language.

When I wrote to Guerrier, a question on his titles were one of my inquiries.

They are quiet in being untitled, but also command a presence. Always starting with “Untitled”, they range in length. A shorter name like Untitled (held within the fold; marks, trace) ii, to a longer one, Untitled (Place, color guarded and latticed, found to be held within the fold) i.

Regardless of length, the parentheses remain. Because parentheses are mostly used for supplementary and non-essential information, I wonder for a second if this is the title’s moment to reclaim its position within the artwork, to fill in what has been withheld by geometrical opacities.

My draw towards the titles is simple: reflex and veracity. Do these words declare a thesis? Are they descriptions to be rendered to the image? Matching title against image, looking for a symbol for impulse after seeing a latticed pattern, perhaps what I am hoping for is fidelity, even didactism, or for the titles to be whispering, with the wisdom of old friends, entry points to the pieces.

To my query on titles, Guerrier told me:

I like titles that extend reading of a work or an image; titles that operate on the works--the connotations generated by two or three words in the title.

So reading between the lines it is, I think of the titles.

To be inferred, to have and to hold but not show, very much rather also like the lines made from folding, opening and closing.

What is it about the representation of something beneath the surface that compels a solo game of hide and seek, a challenge of vision and imagination? There is something behind the velvet rope as we all know, but cannot see.

An exercise in object permanence then.

The Fold series remind us of that.

Annex

Face-lift on 270 Orchard Road, Singapore

ground floor corridor unit

upper level unit

(1) The built environment, coined by architecture academic, Jon T Lang in Creating Architectural Theory (1980), refers to adaptations to the terrestrial environment, including architecture, housing, lighting and landscaping. The built environment artificially changes patterns of human behaviour and human communication.

(2) Anthropologist Edward T Hall in his book, The Hidden Dimension (1977) identified three types of layout patterns in the built environment. Fixed-feature space (immovable features like walls, floors, windows), semi-fixed feature space (like furniture and movable within fixed-feature spaces), and informal space (perceptual, and varies accordingly to the movement of its interactants).

(3) Object permanence, by psychologist Jean Piaget, is the comprehension that objects continue to exist even when they are out of sight, hearing, or any other sense.

Adler Guerrier, born in Port-Au-Prince, Haiti, lives and works in Miami, Florida. Guerrier received a BFA from New World School of the Arts/University of Florida. His work engages the poetics of place and landscape. Guerrier has participated in group exhibitions, including Smoke And Mirrors at Torrance Art Museum, Whitney Biennial 2008 at Whitney Museum, Harlemworld: Metropolis as Metaphor at The Studio Museum in Harlem. Recent solo exhibitions includes Adler Guerrier: Conditions and Forms for blck Longevity at California African American Museum, and Adler Guerrier : Formulating a Plot at Pérez Art Museum Miami. Guerrier is a member of the board of directors of Oolite Arts and Locust Projects.