Engine Running, Machinery Clanking: Committee of Six by Fred Schmidt-Arenales

“There are two settings in Committee of Six.” The voiceover narration is calm, steady, and measured. Seconds in, it is unmistakable that either stage directions or an Audio Description track is being read; the screen remains black as the voice vacillates between describing the setting and the characters yet to arrive wherein. Thus begins a whirlwind of shifts between script and reality in Fred Schmidt-Arenales’ Committee of Six, an experimental docu-narrative that calls to mind the self-referential expansiveness of both Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (dir. William Greaves, 1968) and Close-Up (dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990) while establishing its own entirely unique footprint on historical and fictional reenactment. The filmmaker’s semi-fictionalized account of meetings between three housing-related Chicago committees fills in these tricky, almost-unfathomable gaps that have led and expanded upon housing insecurity and racist legislation in American cities.

Schmidt-Arenales, who received his undergraduate education at University of Chicago, found the beginnings of Committee as a student within the university and its specific location; nestled within Hyde Park on the South Side of Chicago, the neighborhood’s history shows a long struggle between the institution and the public, with institutional interests favoring white upper-class residents. The story of Committee finds its roots in these trappings, with the ambitions of those in power aimed towards keeping lower income minority communities out of neighborhoods like Hyde Park, which happen to be home to prestigious universities. Much like the University of Southern California in South Los Angeles’ University Park neighborhood, the University of Chicago historically relied on segregation and affiliated laws to attract more privilege and funding to their educational community. They wondered, if lower income residents kept moving into the area, would it not hurt the university’s bottom line and their access to donor funding? The film documents this inextricable relationship between the academy (and the bureaucratic structures that reinforce it) and gentrification, which have grown and continued into the present day.

Using the law to facilitate one’s goals is anything but a foreign concept to those of us trapped in the daily news cycle. Historically, urban renewal projects were implemented in the 1950s and 60s to combat rising minority populations by making housing unaffordable and inaccessible. Therefore, the more “fictional” conversations taking place in the film are between three documented entities that were instituted in the 1950s: the University of Chicago, the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference (HPKCC), and the Southeast Chicago Commission (SECC), the latter of which was formed by the university. In Committee, the organizations have convened to discuss concern over the influx of people of color to their neighborhood.

The establishing shot of the film is at eye-level, one of the only instances where we see the full expanse of the conference table at which the performers sit. The table stretches into the background, allowing a quick visual exploration of the setting, which has markings of the mid-twentieth century: brown leather chairs, semi-filled bookshelves, wood flooring. Soon thereafter, performers shuffle into the room in costume, ready to begin their first meeting with the urgency embodied by their characters. Subtitles are automatically provided throughout the film regardless of viewer preference, further cementing accessibility as an integral aspect of the work as a whole. The meeting begins, and we are thrust into the action as if we were seated at the table with the performers.

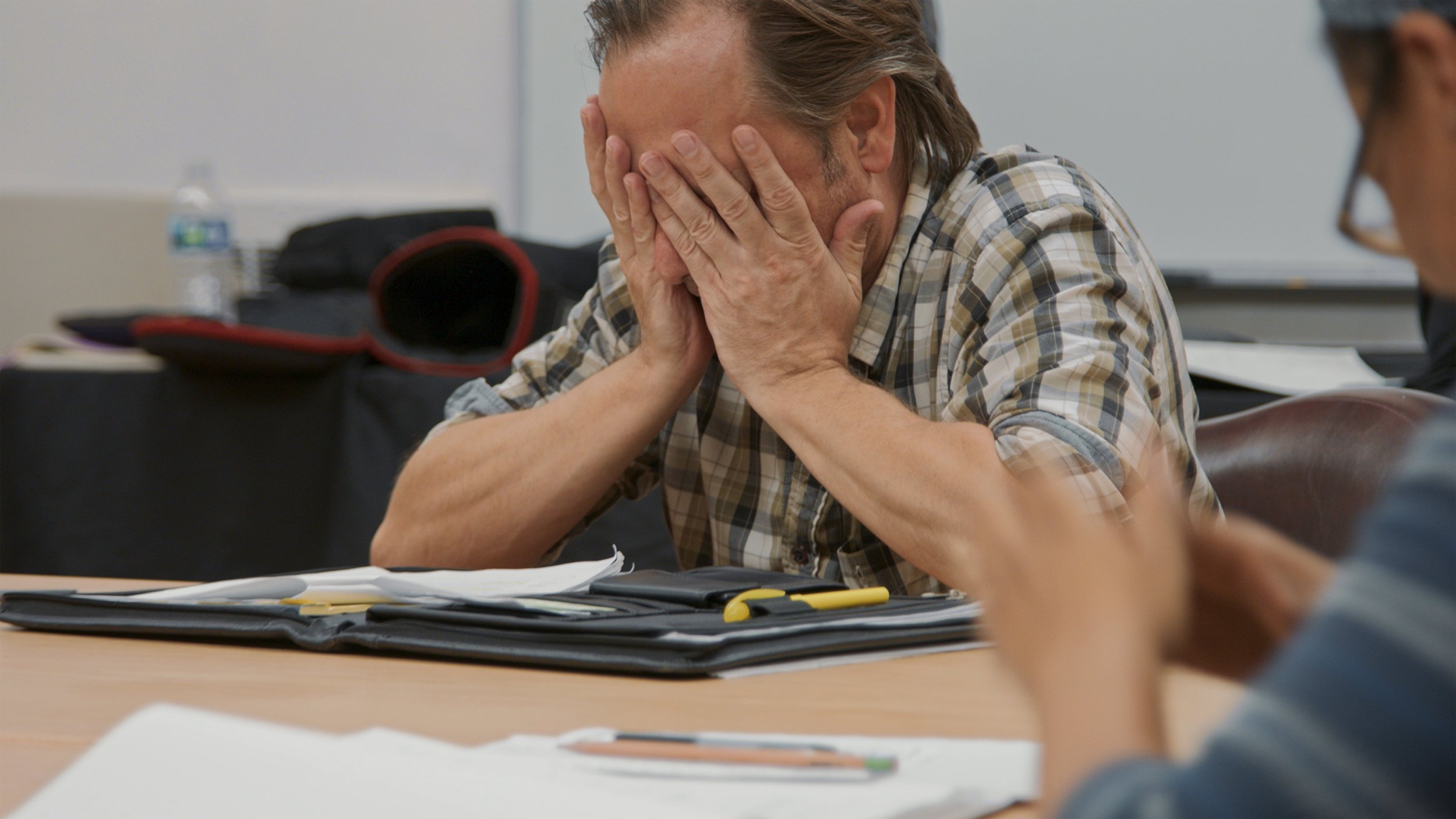

Conversations beyond the scope of the filmed speculative narrative are seen in the meeting room or more casually in the park; here, collaboration between performers, scholars, and activists, flourishes as they question reconstructing and questioning the project at hand. The director both constructs and participates within the film, straddling the line between observer and observed among the actors—it does not take long to hear him on camera or offscreen as he mediates questions from and between performers as they operate within their own meta-committee outside of the narrative. Each participant voices their concerns or frustrations with the archival and scripted materials they have been given.

While straddling the binary of observational cinema verité and the camera as propagator of fictional cinema, the characters are introduced through voiceover, albeit with minimal details expressed. Scripted and candid discussions slowly unravel the roles behind placards in front of them. These discussions naturally evolve into dialogues with lofty questions concerning the problematics that underline each meeting and the proposed agendas for crisis resolution; occasionally these conversations result in casual laughter or disbelief. We can see the performers as people, rather than direct reflections of the characters they play (and, as shown, fundamentally disagree with).

In the aforementioned film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm—a foundational reference for Committee—William Greaves hybridizes documentary and fictional narrative through the camera as a couple (played by actors) repeatedly breaks up; a documentary camera crew filming a crew that is filming a scene for a film. Naturally, passersby stop and watch or interact with the crew, with the charismatic Greaves telling them they could be famous. In the same fashion, Committee switches from narrative to reality often, blurring the lines of what makes reality reality. Similarly, Abbas Kiarostami’s 1990 film Close-Up plays with docufiction to a differing extent; the film documents the trial of a man who falsely portrayed a filmmaker, convincing a family to act in his film. The people involved reenact this ordeal, continuously distorting the notions of fiction and nonfiction.

By exposing these clashes of bodies of community organizers and institutional representatives, Schmidt-Arenales’ approach to narrative is multi-layered and inherently complex due to each fictional party’s co-opting of others’ interests to best serve their narratives. The visual manipulation of time and space contributes to this complexity; there is no written script attributed to these very real meetings that took place in 1955, yet the minutes that have been left to the archive remain as a foundation through which these overlooked historical moments of importance occur. As a viewer, the boundaries between narrative and reality become increasingly difficult to parse through—who are we to be simple bystanders when there is so much more at stake? Cameras are the apparatus through which we, as an audience, identify with to find personal meaning through the narrative. The discussions behind the text therefore become more integral to our understanding of the loosely outlined plot as the plot itself. It feels crucial to identify with the camera in this way—does it focus on a committee member? Does it document a candid off-script discussion? Although the narration pointedly delineates between “reenactment” and otherwise, trust is fundamentally instilled in the act of viewership, piecing together the story of the committee from fragments related to the notated minutes and discussion thereof.

Questions of the biased behaviors and practices that lead to these meetings are ultimately what weave together reenactment and candid discussions. In one instance, the performer playing Farr pointedly asks, “So how is this [justification], so how is this not racism?” in response to actors’ questions surrounding the narrative and their integral part in reconstructing it. It is obvious that the grimy underbelly of “urban renewal” is clearly painted over by the university with language pointing to a growing “crisis” based on race, which becomes more and more clear through the performers’ heightened discussions, rather than the makeup of the reenactments themselves. By interrogating this language that has been loosely mapped out for them through the minutes that have been left behind in the archived agendas, Schmidt-Arenales’ film vacillates between reality and history to find where the two meet and veer away from each other. Speculation and interpretation between those on screen and the audience become grounding mechanisms for the film, both of which are magnified through these unanswered questions of the archival material itself.

As a writer, I often contemplate over focusing on the artwork itself over the history that shapes the work; sometimes they have no relationship to one another, and sometimes they very much do. Committee feels like an inevitability in that we have no choice but to question the construction of the rules and regulations that guide us. Its meta-commentary is layered on top of its meta-narrative and meta-reality; there is no film without the discussions that guide and shape each performance, yet there is no true grappling with these meetings in 1955 without thinking through how they have led us to widespread societal struggle in the present moment. At the film’s end, the characters are frustrated with one another, still struggling to find a solution to the “crisis” at hand. Papers rustle, the performers shoot a wry knowing glance towards the camera, and the film cuts to black.

Erin Gordon, 2023.

——————————————————————————

All images: video stills from

Committee of Six

2022

TRT 40:11 minutes

All images courtesy of the artist

——————————————————————————

Fred Schmidt-Arenales is an artist and filmmaker. His projects attempt to bring awareness to unconscious processes on the individual and group level. He has presented films, installations, and performances internationally at venues including SculptureCenter and Abrons Arts Center, New York; Links Hall, Chicago; The Darling Foundry, Montreal; LightBox and The Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; The Museum of Fine Arts and FotoFest, Houston; Künstlerhaus Halle für Kunst und Medien, Graz; and Kunsthalle, Vienna. Fred is a 2022-23 Core fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

——————————————————————————