Rinsing the Bones

How do I begin? In the guise of the disembodied third-person voice, my words seemingly transmitted from an authority out of nowhere. Or do I choose the first person? A form that acknowledges my subjectivity, recognizing the limits of my unreliable narration while endowing what I have witnessed – my experience. On Saturday, October 21, 2023, I arrived late at the 18th Street Arts Center for Jenny Yurshansky's workshop for her exhibition "Rinsing the Bones." I was at least an hour late, if not more when I hurriedly entered the exhibition space, disorientated and unsure of what to expect. Before I knew it, I was seated on a gray cushioned couch in the center of an equally grayed and dimly lit subsection of the exhibit next to another workshop participant, Tahereh. Already busy at work, I joined Tahereh in the quixotic task of making sense of an overwhelming and confusing patterned needle and thread garment instructions. Tahereh had started before me, and it was clear from the sheer number of lines already sewn into the fabric that someone else had started this endeavor well before her. But there we were, both armed with our needles and threads, picking up from where others had left off, following a confusing set of directions, getting lost in the tangled mess of lines, losing each other, sometimes ourselves, then finding each other again, only to get lost again in the tangled web. We had each been thrust into the middle of a narrative without a preamble; we were in medias res, forced to make sense of the circumstances set by events that had started before either of us had entered the situation.

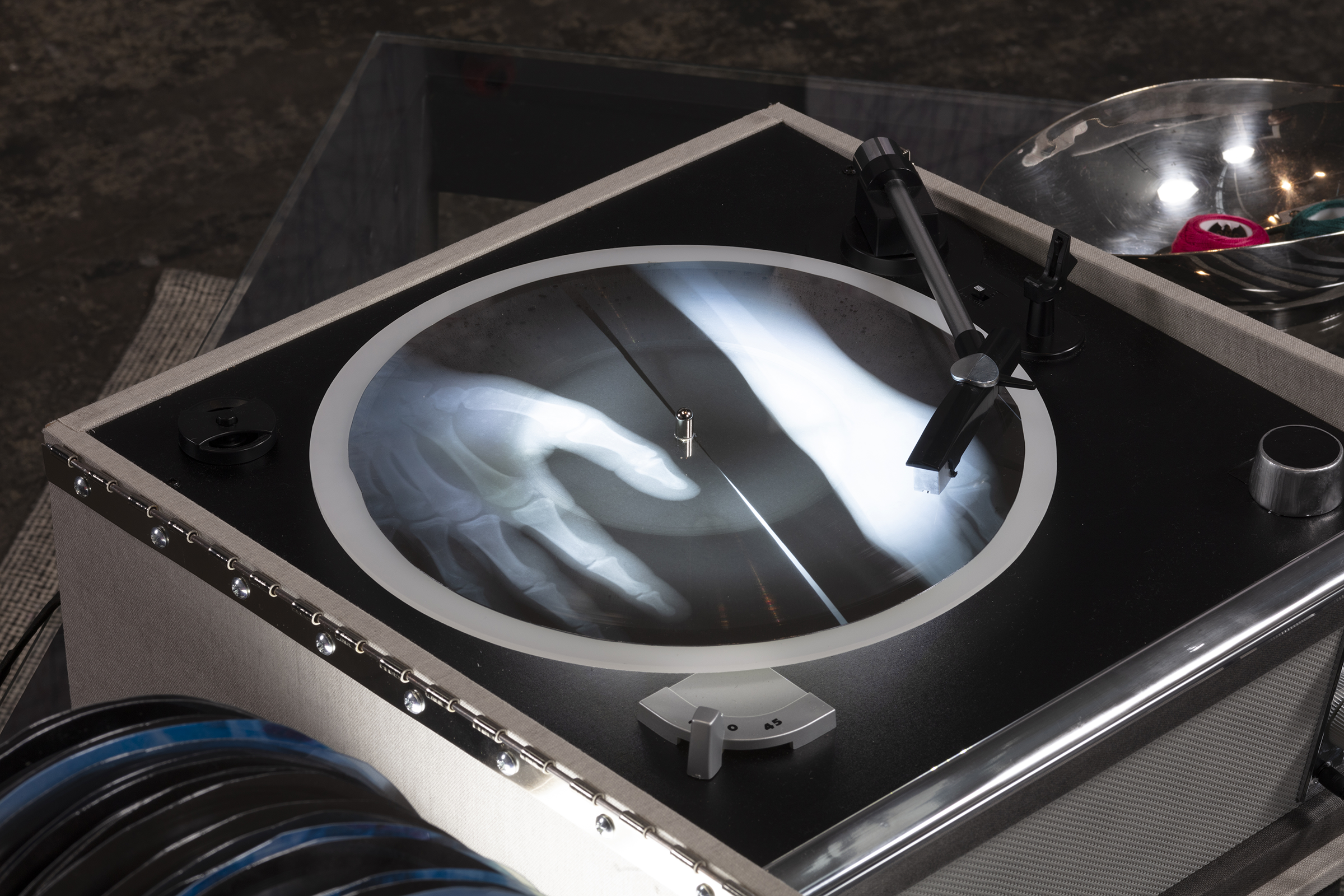

This particular situation had been initiated by the artist Jenny Yurshansky as part of an ongoing project titled "Rinsing the Bones." Yurshansky explains that the phrase is a Russian expression most associated with gossip but that its deeper roots go back to an ancient Slavic burial ritual that involved physically cleaning the remains of a deceased loved one while sharing and recounting their life. Yurshansky was born stateless in Rome while her parents, Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union, navigated the asylum process that ultimately led them to the US. Displacement and migration are thus entry points into Yurshansky's work, yet from there, the story, or stories, move in two directions – both inward and outward. Using her own family's experience as a starting point, Yurshansky's artistic process operates by reaching out to others, strangers in fact, who are asked to share stories about their own family experiences, which then become woven into the tapestry of Yurshansky's ever-expanding collective project. Participants (whose anonymity is safeguarded by Yurshansky) are asked to bring a family keepsake that prompts them to speak about a lost family member for a recorded audio testimonial about their family story. The audio recording is then engraved onto an X-ray film, turning into a functional record that can be played on a turntable (these bone records were technically devised to copy smuggled popular Western music vinyl records under the Iron Curtain.) Yurshansky calls this piece in the exhibition "Generation Loss" – a word-play on the audio degradation that occurs each time a record is played and the dynamics of human lineage – which juxtaposes the emotional and psychological trauma recorded in the personal testimonial to the documented physical injury in the X-ray image. Each bone record is archived in a ghostly listening station resembling a domestic space with a coffee table and sofa (where I sat next to Tahereh).

The participants' keepsake objects previously scanned and 3-D printed into sculptural replicas are now archived in a glass vitrine titled "Rinsing the Bones (Reliquary)." Each replica is printed in white resin and finished by the artist in an ivory hue or off-white bone color to suggest a draining of their earthly function, having been seemingly ossified or rinsed. Rendered as ghostly relics, the objects have been released of their psychic weight. Yurshansky explains how the belief behind the original ancient Slavic ritual of bone rinsing was that, as the details of the deceased person's life were accounted for by their loved ones still on earth, then the soul of the deceased would, in turn, be released and freed to rest. In Yurshansky's rinsing, the aim is to exhume family generational trauma for the sake of those living on earth as much for those no longer on it.

Yurshansky's practice begins in the first-person but, in an interesting twist, bridges into a third-person collective "we" that invites the subjunctive. This begins with her own experience and those of her parents as stateless refugees, as well as the generational trauma these experiences left. Trauma and migration thus form two poles of Yurshansky's work; another way to put it is that the artist begins with the trauma of migration. This is where the double movement of Yurshansky's look inwards into her own family's history across the borders of nation-states meets outwards, to the participants who contributed their families' stories to the work and the viewers who carry their own experiences in. It's at the convergence of this difference – between the first–person experiences of the artist, those of the participants, and the viewers – that a constitutive "we" begins to form. To locate and define what he calls "refugee politics," scholar Hadji Bakara looks to the work of Jewish American poet Muriel Rukeyser and pinpoints her ambivalence towards particular notions of national sovereignty, if not a full-throated rejection, in her poem "Mediterranean," where she names "hypocrite sovereignties," built around the process of exclusion and denaturalization rather than rights and protection. This insight lies in Rukeyser's strategic placement of "we" and "I" in the context of understanding the rise of fascism across Europe on the eve of World War II. Bakara points to Rukeyser's use of "I" in relation to recollection and witnessing, which then shifts to "we," emphasizing the potential ways of being and taking action with others in an uncertain future. It's here, between the "I" and "we" in Rukeyser's poetry, where Bakara identifies a political aesthetic that recognizes how a particularly inherited idea of national sovereignty can offer "a solution to the crisis for a speaking "I" who is "foreign," but it is a catastrophe for a plural "we" that includes refugees, and for all future peoples seeking refuge." [1] Far from didacticism, the political implication of Yurshansky's project reveals the potential bonds possible between those that might be formally considered under refugee status and "all future peoples seeking refuge." [2] Here, it is useful to expand on what migration means beyond just crossing external national boundaries but also the internal and psychological borders within oneself. Francis Stoner Saunders describes borders as scars and "explanations of identity," she goes on to explain that "[we] construct borders, literally and figuratively, to fortify our sense of who we are; and we cross them in search of who we might become." [3] Migration can, therefore, be understood as a defining attribute of what it means to be a human being, an experience marked by crossing thresholds as much as constructing them, and in which scarring and trauma are unavoidably what it means to be a person.

"Writing at the end of the twentieth century, Edward Said stated, "Modern Western culture is in large part the work of exiles, émigrés, refugees." [4] If the story of the twentieth century is to be understood as one in which a world of empires became a world of nations – spurred by the emergence of industrialized warfare, the administrative shift from subjecthood to citizenship, and the universal acceptance of the passport – this also marked, what scholar Saskia Sassen describes as "the beginning of the modern refugee crisis as we have come to understand the term today." [5] With nowhere to go, the wandering humanist in exile was now the stateless figure. And as the world was reshuffled by two total wars, a luminous chorus of thinkers set out to understand this new political figure of the refugee and the art, literature, and poetry produced around them, not only Rukeyser but also Hannah Arendt, W.H Auden and later Flanery O'Conner, John Berger, Giorgio Agamben, and Edward Said, among many others. Said shrewdly noted that scale makes this new age of the refugee distinct from the age-old condition of exile. For Said, the challenge lies in the fact "[that]exile is neither aesthetically nor humanistically comprehensible: at most [it] objectifies an anguish and a predicament most people rarely experience first-hand;" he goes on to caution that a literature of exile must resist the temptation to romanticize the figure of the refugee, which risks "to banalize its mutilations, the losses it inflicts on those who suffer them." [6] Back in Yurshansky's exhibit, lost in the disorientation of an absurdly confusing overlay of Soviet-era sewing patterns on my lap, but also lost in pleasant conversation as I learned more about my workshop colleague Tahereh, I caught a glimpse into a humanistic comprehension within, and despite, this disorientating scale. Yurshansky titled this work — where Tahereh and I sat — "Wayfinding."

I would later learn that Tahereh was particularly unique among the over three hundred other participants in that she was part of a collective that Yurshansky had invited to share the exhibition with. Named The Running Stitch and founded in 2001 for their love of quilting, Tahereh Sheerazie was among the founding members, all Muslims from different countries who live in the Los Angeles area. Along with her, the current members are Jane El Farra, Anjum Khan, Aida Osman, Ramza Saliefendic, and Sobia Shehzad. Tahereh did not immediately reveal this fact as she watched me struggle (most likely humorously) to simply thread a needle, the simplest sewing task. Instead, and most certainly because of the framing of Yurshansky's exhibition, our conversation meandered around each other's narrations of our own lives, catching small overlapping points of commonality despite our vastly different sets of experiences and identities. This is precisely the experience I had while listening through the archive of recorded testimonials or "bone records" by the rest of the contributing participants. As engaged as I was listening to someone describe her mother's cooking spoons, I have little to nothing in common with the daughter of a Polish Holocaust survivor – likely the precise reason why I found her story so engaging – and yet something inside me shifted in recognition towards my own family dynamic when she described her mother's desire to protect her from sadness in the family's past. This tension between the particulars and the universals provides so much meaning in sharing stories. You tell me your story and, by doing so, expand my understanding of the world beyond myself to your world, filled with things I had no concept of. But when either of us least expects it, something in your story overlaps mine, and now our worlds resemble each other a little more.

Many of the quilting projects by The Running Stitch were created as charitable works made in response to varying natural disasters and crises around the world: the 2003 earthquake in Baam, Iran, an earthquake in Pakistan in 2005, Hurricane Katrina in 2006, and the recent floods in Bangladesh. But the historical backdrop for the coming together of this Muslim women's sewing group was marked by two world historical events, or crises, which were not natural disasters: the attacks of the World Trade Center in 2001 and the Second Intifada that began in 2000 and lasted till 2005. The day I sat lost in Yurshansky's "Wayfinding," it had been exactly two weeks since Hamas' attacks on Israeli civilians on October 7. As I write this, it is now week ten of Israel's devastating retaliation in Gaza. Indeed, the politics of exclusion and sovereignties of hypocrisy that Rukeyser loathed, seems relentlessly ascendant. The quilts of The Running Stitch hang outside the dimly lit exhibition spaces of Yurshansky's "Wayfinding" and "Rinsing the Bones (Reliquary)." In sharp contrast, this room is bathed in natural light with the quilts displayed along the walls. In the center of the room hangs a massive Möbius-shaped quilt sculpture by Yurshansky made with collaborators titled "Unfolded Narratives." Not unlike many of the other works, this physical object is also the outcome of numerous interdisciplinary workshops organized by Yurshansky, held in various institutions across Los Angeles. This is underscored by the workshop table, chairs and material in the corner, where the work is still very much activated. What sets "Unfolded Narratives" apart from the intimate one-on-one testimonials of "Generation Loss" is the former's reliance on group dynamics. As explained by Yurshansky, this workshop begins with participants discussing the complexities of home, origin, and identity across their different experiences. The contingent historical and geopolitical specifics of one set of experiences to another's – how they differ and what they might share – falls into sharper relief as the patchwork of all the individual family stories becomes visualized together through the quilting work. To employ the phrase, the personal is political. Yurshansky's "Unfolded Narratives" reveals how our individual lives are already interwoven within the social fabric.

Throughout Yurshansky's exhibit, I was reminded of Bolivian sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui's metaphorical description of weaving, understood as a feminine practice of intercultural coexistence. Central to this is the Aymara word ch'ixi and its many connotations, one of which is a heather gray color in fabric making that appears as a mix of contrasting colors when, in reality, each color is separate yet tightly arranged and juxtaposed together. [7] For Cusicanqui, just as Rukeyser, this is fundamental for the making of a constitutive "we," a situation in which the figure of the refugee, or those seeking refuge, can understand their place in the world and not simply passively experience history but can actively make it. Through the prism of Cusicanqui and Rukeyser, Yurshansky's artistic practice of weaving narratives moves beyond metaphor through its additive quality. Here, I use the word practice in a very specific sense. The collection of testimonials increases as more voices are included in each incarnation of the work. With every story, every experience that becomes part of the work, another threshold is crossed, from participant to viewer – one witness at a time. The tapestry expands. This is the definition of a feminist practice, not in the biological sense but in the political. Cusicanqui argues that the notion of identity for the masculine is tied to territory, whereas the feminine identity is tied to fabric. [8] Identity comes not from anything fixed or static but is, of course, constructed or crafted, it is a practice that operates in relation to, and with others. Responding to the disorientation of the first half of the twentieth century during World War II, Rukeyser concludes her 1944 poem "Letter to the Front” on her experience of being a woman, the masculine, the feminine, and the fragile relationship between memory and the future.

10

Surely it is time for the true grace of women

Emerging, in their lives' colors, from the rooms, from the harvests,

From the delicate prisons, to speak their promises.

The spirit's dreaming delight and the fluid senses'

Involvement in the world. Surely the day's beginning

In midnight, in time of war, flickers upon the wind.

O on the wasted midnight of our pain

Remember the wasted ones, lost as surely as soldiers

Surrendered to the barbarians, gone down under centuries

Of the starved spirit, in desperate mortal midnight

With the pure throats and cries of blessing, the clearest

Fountains of mercy and continual love.

These years know the separation. O the future shining

In far countries or suddenly at home in a look, in a season,

In music freeing a new myth among the male

Steep landscapes, the familiar cliffs, trees, towers

That stand and assert the earth, saying: "Come here, come to me.

Here are your children." Not as traditional man

But love's great insight —"your children and your song"

Ryan S. Jeffery

December, 2023

—————————————————————

References:

[1] Hadji Bakara, "Refugee Politics," Journal of Narrative Theory, Volume 50, Number 3, Fall (2020) pg. 138 - 147

[2] ibid

[3] Francis Stoner Saunders "Where on Earth Are You?" London Review of Books Vol. 38 No. 5 March 3, 2016

[4] Edward Said "Reflections on Exile" Reflections on Exile and Other Essays Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press 2000 pg. 173

[5] Saskia Sassen Guests and Aliens New York, NY; The New Press 1999 pg. 78

[6] Said pg. 174

[7] See Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui "Ch'ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization" South Atlantic Quarterly (2012) 111 pg. 95–109

[8] ibid

——————————————————————

Image list:

1- Generation Loss, 2023

Modified record player, LEDs, acrylic, steel, wood, 61 X-ray film records, audio recordings of interviews with Rinsing the Bones workshop participants

2- Wayfinding, 2023

Five Soviet sewing patterns printed on linen, embroidery thread, aluminum

3- Rinsing the Bones (Reliquary), 2023

3D resin prints, alcohol ink, glass, mirrors, aluminum, steel, and shadows. Reliquaries of

family keepsake objects selected by Rinsing the Bones workshop participants

4- Rinsing the Bones (Reliquary), 2023

(detail)

5- Quilts by members of guest artist collective The Running Stitch

Core and present collective include Jane El Farra, Anjum Khan, Aida Osman, Ramza Saliefendic, Tahereh Sheerazie, Sobia Shehzad

6- Unfolded Narratives, 2023

Original printed cotton fabric, batting, thread, plexiglass, steel cable wire

All images courtesy of Joshua Schaedel.

————————————————————————————

Jenny Yurshansky, Jenny Yurshansky is an American artist who was born stateless in Rome by way of Soviet-era Moldova. received her MFA in Visual Art from UC Irvine in 2010 and was a post-grad in Critical Studies at the Malmo Art Academy. Her previous solo exhibitions include: There Were No Roses There, American Jewish University (2022), Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory, HarvardWestlake School in Los Angeles (2020), and Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory in the Emerging Artist Series, Pitzer College Art Galleries (2015), and the Stockholm Royal Institute of Art (2015). Recent projects include a new commission We are all guests here for a group exhibition at Bridge Projects (2021) and a series of over 40 virtual workshops during COVID hosted on behalf of the American Jewish University, Fulcrum Arts, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, the Museum of Art and History in Lancaster, Pitzer College, and other institutions offering the public a way to maintain a sense of community, connect to the issue of social justice, and participate in somatic activities that focused on breath and landscape.