Bad Outdoorsmen, John Muir, Alone, and the Outdoor Industrial Complex

Meredith Laura Lynn and Katie Hargrave met as graduate students in 2010. In 2017, they attended a residency in Oregon that connected artists with the environment. On the way there and heading back east afterward, they stopped in national parks and conceived what became their ongoing, long-distance collaboration. Lynn now lives in Florida and Hargrave in Tennessee. They often develop ideas and conduct research in the field then take on developmental parts of projects separately and join forces at crucial junctures on visits to each other’s studios, camping, or in culminating moments for exhibitions. Their work takes critical journeys through historical and contemporary ideas about human connection with nature. They’re fascinated by the stories Americans tell—and are told—about land.

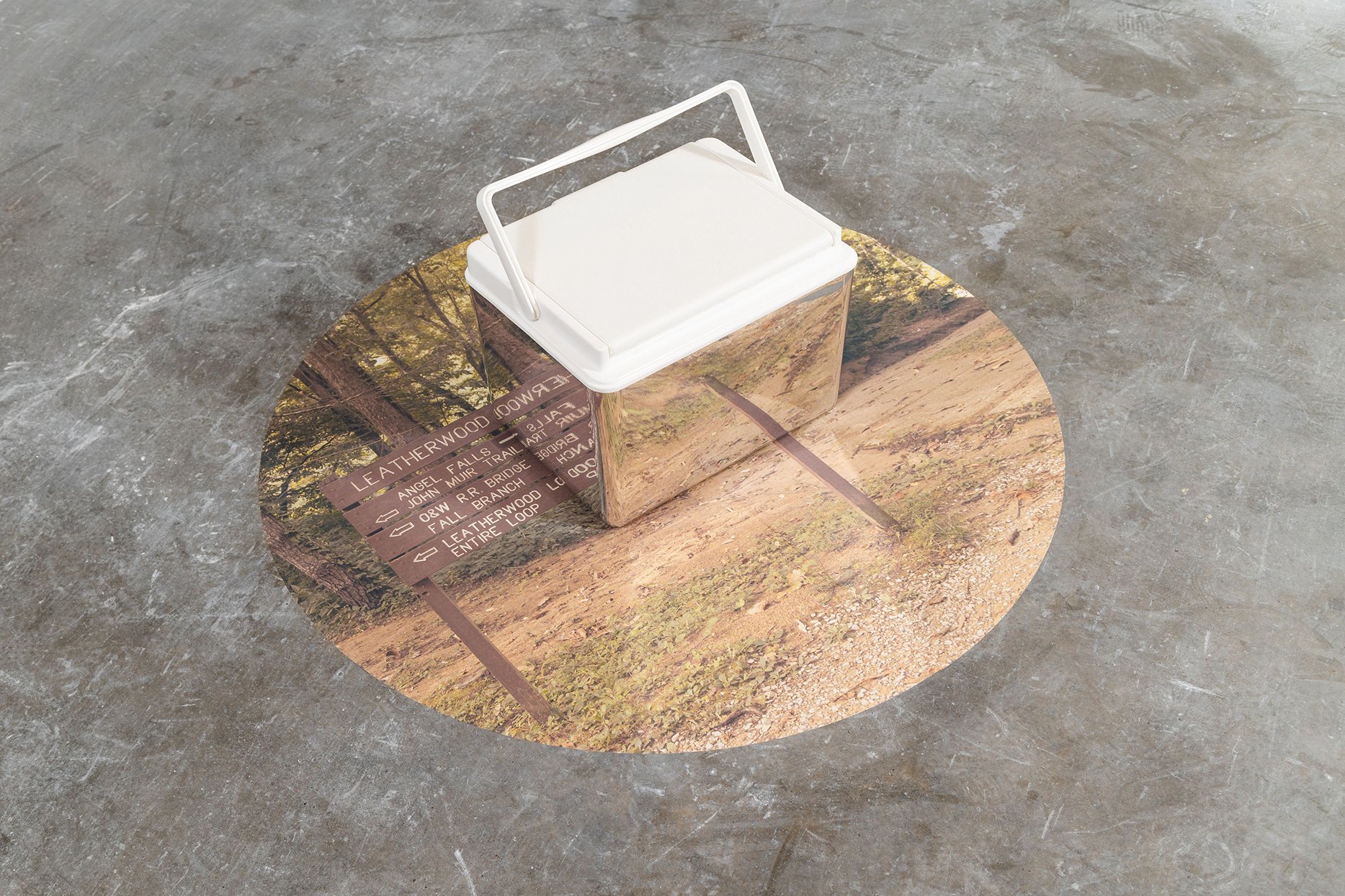

In Lynn and Hargrave’s 2021 work, Preserving, a portable cooler with a mirrored surface sits on top of a round photograph on the floor. The image shows a trail sign announcing Leatherwood Loop and John Muir Trail. The insulated container partially disappears into the photograph, complicating the image, confusing the sign’s intentions, and bouncing back human failings—evidence of what the artists called on a recent podcast the “outdoor industrial complex.” Following the words Leatherwood and John Muir Trail are their mirror images. Significantly, the path named for author, naturalist, and denounced Sierra Club co-founder John Muir lies on the floor next to its reflection. The cooler casts back a name now associated with a fraught legacy. Many these days consider Muir a racist. In Preserving, what is preserved? Muir? His legacy? Land? And/or lunch? In an artists’ talk at Flagler College, Lynn and Hargrave described how their use of mirrors relates to wordplay. Say the name “Muir” and the word “mirror.” They sound alike. The artists use mirrored materials and Muir-ored materials. When we go outdoors, like it or not, we might see or experience evidence of Muir and his thinking.

Muir is a stand-in for the outdoors itself the way Shakespeare is a stand-in for love. People quote Muir the way they quote Shakespeare at weddings. Maybe they’ve never read or seen any Shakespeare. It’s similar with Muir. Generally, people don’t know much about him, but he’s a go-to when they want to signal “nature.” We don’t know the extent to which the outdoor industrial complex is shaping our activities. When we grab our cook sets, water bottles, and tents and say we’re going camping to be rejuvenated, we might be about to fall into even more than a cliché. We could also be spiraling into a problematic history.

Muir had the ear of another racist figure, the imperialist big game hunter and US President Teddy Roosevelt. Muir and Roosevelt worked together with others to establish the National Park Service and millions of acres of national forest in the early part of the twentieth century. Muir is credited for his influence on the conservation movement that has fought to keep water clean, wildlife from going extinct, and pollutants out of the atmosphere. In 2020, the Sierra Club distanced itself from Muir’s derogatory comments about Black and Indigenous people. Still, Muir is everywhere. Walmart sells a Lucky Bums brand “Muir” sleeping bag for kids, there are John Muir bumper stickers, and John Muir College at the University of San Diego is named for the outdoorsman. The college motto is “Celebrating the Independent Spirit.”

Lynn and Hargrave point to lionizations of Muir on the survivalist envirotainment reality show Alone, which premiered in 2015 and starts episodes with quotes by Muir and a vast and curious array of writers, philosophers, and world leaders. Many of these episode intros would work well in a post-apocalyptic training camp. Take season three. There’s Napoleon (“The first virtue in a soldier is endurance.”) and Flannery O’Connor (“If you don’t hunt it down and kill it, it will hunt you down and kill you.”). I spotted Muir’s words in season five (“The mountains are calling, and I must go.”), season eight (“Only by going alone in silence, without baggage, can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness.”), and season nine (“And into the forest I go to lose my mind and find my soul.”).

Lynn told the magazine Dovetail in spring 2023 that she and Hargrave were reading A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf, Muir’s chronicle of his exploration of the American South. Muir started the text in 1867 when he was twenty-nine. Reading it prompted Lynn and Hargrave to think critically about “people, usually white men,” they said, “who we uphold as somehow being better at being outside than the rest of us.” In his travel diary, published after his death, Muir made extensive, sometimes gleeful botanical observations. “How little we know as yet of the life of plants—their hopes and fears, pains, and enjoyments,” he remarked upon coming across nearly twenty-foot-tall vegetation.

Perhaps because Muir spent much time musing and getting his thoughts down rather than foraging or making camp, he was often hungry and cold. He pressed Southerners he encountered for food and lodging, even though they seemed themselves to be just scraping by. And although Muir avoided political debate, he commented on the burnt fences, trampled woods, and other physical scars evident in the American post-Civil War landscape. His descriptions of the people he met are condescending and racist. A Florida entry described the night as mysterious, wet, and thick. Without a place to stay indoors, he was afraid. He wrote that he thought Black people would attack him in the dark. Lynn explained further in Dovetail, “It’s clear that he’s actually not very good at being outside. He’s not very good at camping. His brother has to wire him money because he has to pay to stay in inns and buy food.” Lynn and Hargrave find Muir not only racist but also inept, entitled, and classist.

Bad Outdoorsmen, Episode 1, 2022, is a three-channel video installation created by and starring Lynn and Hargrave. One section mimics the confessional Blair-Witch-like footage from Alone. Another takes the format of an audition for the production. The artists wear camouflage they constructed using cutout fabric leaves—shimmering blurs of purple, gray, and green. They generated these from screenshots of Alone. The custom camouflage costumes resemble hunters’ or sharpshooters’ attire—ghillie suits, as they’re called. When I chatted with them online, Lynn and Hargrave told me Muir was born in Scotland where the suits are said to originate. In those days, the ghillie would scout big game that the gentry could then kill. For Lynn and Hargrave, wearing their versions of the suits helps them get into character. It also makes them look like Alone superfans, underscores the violence implied in wilderness fantasies, and suggests in a tongue-in-cheek way that they could at least blend in on Alone, although no one wears a ghillie suit on the show.

Maybe Lynn and Hargrave wouldn’t win on Alone. But why couldn’t they try? Hargrave shared with me on our video call that she can start a fire with a flint. She can also identify plants, forage, and find fresh water. Lynn grew up fly fishing. “There’s a category of people on Alone who will last a really long time because they can deal with starvation. They have a high pain tolerance,” Lynn explained, “Katie would fall into that category.” Yet, at this point, Lynn doesn’t want to fully buy in. She shared her experience watching the two seasons of Alone where contestants return. Many seem to show up with PTSD and other health problems from what happened in previous seasons. Lynn’s in no hurry to do anything like this to herself.

As a show, Alone is wildly popular, even if it’s dangerous for contestants and promotes both the idea that nature is cruel and the type of the supposedly robust individualist explorer. Season 11 is in the works, and the History Channel, which produces Alone, has rolled out several spinoffs. Each season, contestants compete to see who can stay in a particular unforgiving geography the longest. The hopeful film their progress. Extensively. Night and day. They’re alone, of course, but the video keeps them somewhat tethered. They also wear GPS trackers and receive periodic medical visits. The prize? Half a million dollars.

An August 2023 article in Vulture called the show “an exercise in controlled dying.” I went to a strange place binge-watching it over a long weekend. I’m usually not a reality TV guy, but I’m suggestible, and I’ve had more than my share of romantic illusions. As the episodes stacked up, I caught myself trying to ration servings of soup. In literature and pop culture, when groups get stranded on islands, they start tearing each other apart. Alone demonstrates that when an individual is similarly stranded, they starve and tear themself apart. Although the program maintains that the contestants are trained survival experts, since the weather and terrain are taxing, food is hard to get, and they don’t eat enough. They get weaker and weaker. They slip and make bad decisions. Setbacks hurt their confidence. They get scared, confused, and become self-critical.

Spoiler Alert: Roland Welker, 47, of Alaska, lasted one hundred days on Alone and feasted on musk-ox. Nicole Apelian, 48, from Washington state, caught salmon from the same stream where bears were fishing, but she and Welker are exceptions. Some contestants have scarfed down mice and slugs. Jose Martinez Amoedo, 45, from Spain, tapped out when he fell out of a boat he built. Are these pathetic souls or poets? “This cove is my universe, and I have to adapt myself to it,” said David McIntyre, 50, a father from Michigan, after watching and admiring beavers swimming. McIntyre decides if he can’t somehow train the beavers to work for him, he should become more like them. Beavers don’t fail. McIntyre wanted to use his prize money to spoil his kids a little, to be “the dad of yes.” He didn’t like being the opposite, “the dad of no.”

In The New Yorker, in September 2023, Jay Caspian Kang wrote that the most macho men tend not to fare well on Alone. “Although I’d stop short of saying that the show is feminist,” he wrote, “the producers and editors do seem to relish in cutting the most annoying survivalists down to size.” Much of what we watch on Alone, and what works well for the contestants, is mundane. So, why is Alone popular? In the Guardian in 2001, Salman Rushdie warned that reality TV is gladiatorial combat. He posited, “If we are willing to watch people stab one another in the back, might we not also be willing to watch them die?” In other words, those of us watching reality TV are not heroes. We’re more like buzzards. The more I watched Alone, the more I felt like the show was punishing contestants for something, maybe even mocking them. But for what? Needing money? Trying and failing? If I say to myself, “That’s stupid, they went into an outdoor prison voluntarily,” and then they do poorly out there, that proves my point and reassures me about my different lifestyle choices. So then I get to say they shouldn’t have gone in the first place. They’re going to the wilderness. They buy into some foolhardy notion of their independence. They think they can be sharper, luckier, and hardier than anyone else.

For Lynn and Hargrave, the biggest problem with Alone, John Muir, and his followers is that they all start to feel like accomplices, foot soldiers for settler colonialism. Is it only a sloppy accident that Alone starts episodes with head-scratching quotes like Teddy Roosevelt on courage and Napoleon on soldiering? Napoleon was a survivalist only in the bloodiest terms. When he went outside, he went to conquer. When we get sucked into Alone, how much are we reliving violent, colonialist pioneer fantasies? Maybe that’s why Alone plays on a so-called history channel. It’s a continuation of history.

I asked Lynn and Hargrave, “When I’m watching Alone or if I’m a contestant, do you think on some level I’m thinking that I’m a pioneer? I’m not just a survivalist, or admiring survivalists, I’m having colonial fantasies?”

Hargrave answered, “I think so. Yes. Self-sufficiency is a fiction. If you look at the way that Indigenous people lived, they’re in community with other groups. They’re moving around.” Lynn added: “In order to settle the West, there needed to be the creation of this myth that this land was empty, that there were no people there. So, this becomes fundamental in the creation of the National Park System, the idea that this land is empty. It’s not been domesticated in any way. It’s not been altered by humans. But this is not true.” Hargrave summed up, “Wilderness is a fiction created by America and then exported to other developed countries. Alone is playing into that. The show is rooted in a romanticization which is tied into histories of settler colonialism.”

In that case, Lynn and Hargrave provide an important dissenting vote against Alone. They expose fantasies where they are lodged. They make the outdoors more real, less of a game.

Notes on Sources:

I spoke with Lynn and Hargrave on video calls on November 13 and December 19, 2023. You can hear the artists on the December 4, 2023, episode of the Highlander Podcast available here. A 2023 interview conducted by Kate Mothes for Dovetail is here. Their October 18, 2022, artists’ talk at Flagler College is here.

Alone streams on the History Channel and elsewhere. Nicholas Quah’s August 2023 article, The Making of “Alone,” the History Channel’s Reality TV Show, is on Vulture. Why Alone Is the Best Reality Show Ever Made, by Jay Caspian Kang, appeared in the New Yorker in September 2023. Reality TV: A Dearth of Talent and the Death of Morality, by Salman Rushdie, was published in the Guardian, in June 2001.

About Muir and the Sierra Club, you can read more here. A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf, by John Muir, was published by Houghton Mifflin in 1916.

All Images Courtesy of the Artists:

1. Preserving (2022)

Cooler, mirror vinyl, inkjet on decal

2. Bad Outsdoormen, Episode 1 (2023)

Three-channel video, laser cut fabric, found camera equipment

3. Video Still (1) from Bad Outdoorsmen (2023)

4. Video Still (2) from Bad Outdoorsmen (2023)

5. Video Still (3) from Bad Outdoorsmen (2023)

Meredith Laura Lynn and Katie Hargrave are artists and educators who work collaboratively to explore the historic, cultural, and environmental impacts of so-called public land. Their work has been shown at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (Salt Lake City, UT), Knoxville Museum of Art (Knoxville, TN), Atlanta Contemporary (Atlanta, GA), the Wiregrass Museum of Art (Dothan, AL), Gadsden Museum of Art (Gadsden, AL), Austin Peay State University (Clarksville, TN), House Guest Gallery (Louisville, KY), Granary Arts (Ephraim, UT) and has been published by Walls Divide Press and Epicenter. Their work has been covered in press including Burnaway, Art Papers, Dovetail, Ruckus, New Art Examiner. Together they have been artists in residence at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum (St. Augustine, FL) and Signal Fire (Portland, OR). Hargrave is based in Chattanooga, TN and recent exhibitions include The Front (New Orleans, LA), Neon Heater (Finley, OH) and Alabama Contemporary Art Center (Mobile, AL). She has been an artist in residence at Epicenter (Green River, UT), Hambidge Center for the Creative Arts (Rabun Gap, GA), and the Vermont Studio Center (Johnson, VT). Lynn is based in Tallahassee, FL. Her solo work has recently been shown at the Morris Graves Museum of Art (Eureka, CA), Miami University of Ohio (Oxford, OH), and the Alexander Brest Gallery (Jacksonville, FL). She has been artist in residence at the Jentel Foundation (Sheridan, WY), the Kimmel Harding Nelson (Nebraska City, NE), and the Vermont Studio Center (Johnson, VT). Hargrave and Lynn met at the University of Iowa, where they both earned MFAs.