Forgetting Until Tomorrow

“We comfort ourselves by reliving memories of protection. Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.”

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

According to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, the noun index is defined as “a list of names or topics that are referred to in a book, etc., usually arranged at the end of a book in alphabetical order or listed in a separate file or book.” Based on this description, anything that can be named can be organized in a linear sequence and, consequently, can be categorized and potentially consigned to obscurity through archiving. An insinuation that there is a range of visibility, and equally so, invisibility, that comprises this system of classification leads to a more investigative inquiry about how and what kind of value is being placed on the content being indexed. Rosalind Krauss (1977), in her seminal article titled Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America, differentiates indexes from symbols by highlighting their importance about or reference to a specific source or category. She describes indexing as “the object they signify.” Therefore, unlike a symbol, which represents something else, an index serves as direct evidence of the existence of a particular thing. From this point of view, the proof that something exists is exemplified in the indexing itself.

These fundamental properties or conventions that establish the existence of an object, topic, or name align with the empirically driven sociological theory of positivism. This philosophical movement asserts and values knowledge and reality as only that which is observable, measurable, and understood through logical and sensory evidence. Similarly, indexing supports these shared epistemological principles by excluding intuition, subjectivity, and personal experience as sources of knowledge. When considered within a positivist framework, could indexing provide a framework for dismantling a particular Western cultural narrative that emphasizes universal truths grounded in quantitative data and replicability?

Enter into An Index of Americanisms, a four-piece installation and solo exhibition by Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Rachel Zaretsky. Drawing on statistical data from the National Gun Violence Archives, local and national news reports on mass shootings in 2023, the sociological context of curated memorials, and the diverse responses observed at commemorative sites, Zaretsky’s works advocate for a reflective approach when engaging with each piece as a distinct entity. Concurrently, the works interact with one another, at times silencing an intuitive wellspring of emotion through the stark, compressed presentation of the materials. As illustrated in the exhibition title, An Index in Americanisms is also the name of the 27-foot-long itemized receipt installation. This receipt lists victims, shooters, and injured survivors in anonymous headlines, serving as depersonalized reminders that those who were nameless are now recorded as the deceased. What distinguishes each event is a formulaic record of the location, date, and numerical details of those involved in the shootings, presented week by week. Occasionally, a counterfeit coupon is interspersed among the printed text, omitting descriptors that would humanize the individuals mentioned in the headlines. Can authentic grief for the nameless be felt when the anonymous list appears endless?

Highlighting the absence of preventative measures that could have reduced the number of victims of gun violence throughout 2023, the scroll monument conveys a bleak, sorrowful quality. Draped from the ceiling, casting subtle shadows in the corner where two walls converge, an emotional restraint is conveyed despite its considerable length. This exhaustive enumeration of unidentified body counts under the mass shooting verbiage raises questions about the interpretation of repetition. Since the term "mass shootings" began to be widely used in the 1980s, its definition has evolved in terms of outcomes, intent, and time frame, though the number of victims has stayed consistent (Fox & Fridel, 2022). It is not surprisingly that the voice to define this late 20th-century phenomenon was the Federal Bureau of Investigation, stating that a firearm attack must be intentional, have a fatal outcome, and involve four or more victims in a single incident within 24 hours (Ressler et al., 1988). Due to the rise in gun violence in public areas, the National Gun Violence Archive, established in 2013, redefined a mass shooting as an incident where four or more people are shot, regardless of whether the injuries result in death. Zaretsky’s exhibition delves into how the indexing of mass shootings is influenced by what is deemed valuable through visibility and how details become recognized as facts. It also reflects the grief surrounding what is left out, forgotten, or unimagined. After all, mass shootings were not widely recognized in the language used to report shootings of four or more individuals in communities historically affected by systemic racism.

It would be a significant oversight not to acknowledge America's history of compulsively glorifying racial violence while neglecting to classify such incidents as mass shootings. This bias is apparent in the way certain tragedies are labeled and highlighted according to specific demographics, while other forms of violence, like gang state and police brutality, are frequently overlooked or reframed using different terminology. In his early work on repetition compulsion, Sigmund Freud (1958) explores how unconscious patterns can drive individuals to reenact past experiences rather than merely recalling them, as discussed in "Remembering, Repeating, and Working-Through." Similarly, postcolonial philosopher and literary critic Édouard Glissant (1997) describes repetition as the continuous reassertion of something previously expressed, reflecting a commitment to an “infinitesimal momentum.” While Zarestky’s Index receipt records headlines of mass shootings, a function of the document is to confirm that a transaction has occurred. Labeling the nameless as transactional property and linking deaths with sympathy cards and Getty Images reveals a pattern deeply rooted in America's capitalist foundations. This pattern can be traced back to the nation's origins, including the exploitation and dehumanization that followed the Middle Passage. The recording of slave deeds as chattel records was an early instance of American indexing practices, where repetition and erasure played central roles. Historical issues of indexing are confronted by art historian and curator Bridget Cooks’ and Sarah Watson’s reimagining of classification and information retrieval in her anti-colonialist text The Black Index (2021). Although Zaretsky’s Index receipt points out the recorded unnamed deaths and implies an exchange in the transaction, it neglects to address this aspect of America’s history of repetitive behavior.

When viewing the Index receipt, it is useful to consider how it engages in dialogue with two other works. Sympathies for [Reserved for Name] is a flat, stationary catalog-like photograph on dibond, a picture of an assemblage of brightly colored store-bought condolence cards and coupons on a cork board. A Rose for the Next Tragedy is a free-standing display holding multiple memorial bouquets filled with faux flowers for visitors to take in anticipation of a future loss. On the one hand, the Index points to the grim economic system that profits from loss and grief in the form of product consumption. Alternatively, there is an offer to delve into one's inner world of imagination to nurture what French philosopher Gaston Bachelard (1994) described as the "poetic image," which, as he explained, emerges from language and transcends its conventional meaning. This can be done by using a rose as a tool to envision and explore the mourning process. Unlike being in a state of melancholia, where grieving remains at the level of the unconscious, mourning is a conscious process of grieving the loss of a loved one and coming to terms with the acceptance of an internal change within (Freud, 1917). Mourning can be experienced through exploring language, poetic imagery, or what American psychologist James Hillman (1975) described as uncovering the soul: "the imaginative potential within us, experienced through reflective thought, dreams, images, and fantasy—seeing all realities as fundamentally symbolic or metaphorical." The process of mourning can then begin for those who decide to take, and thereby psychologically receive the possibilities of what the rose may hold.

Zaretsky’s aim to highlight a form of indexing related to mass shootings and public grief—through the muted curation of memories or, the act of un-remembering in the public sphere is further emphasized by evoking a collective ritual overshadowed by unresolved gun violence. She describes sympathies for [Reserved for Name] as “unbearably composed,” a sterilization of tragedy conveyed in printed floral motifs and italic fonts that attempt to provide a placid tone. By avoiding the messiness of fumbling to find comforting words through intimate conversations, a sympathy card simply stating “I wish I knew what to say” starkly contrasts the spontaneous vulnerability of embodying that which is difficult to articulate. Piles of cards are pinned in orderly placements while advertisements showcase floral arrangements and instant delivery needs “for every occasion.” Bundled gifts that lack personal significance fail to distinguish the emotional depth of a funeral from that of an office party.

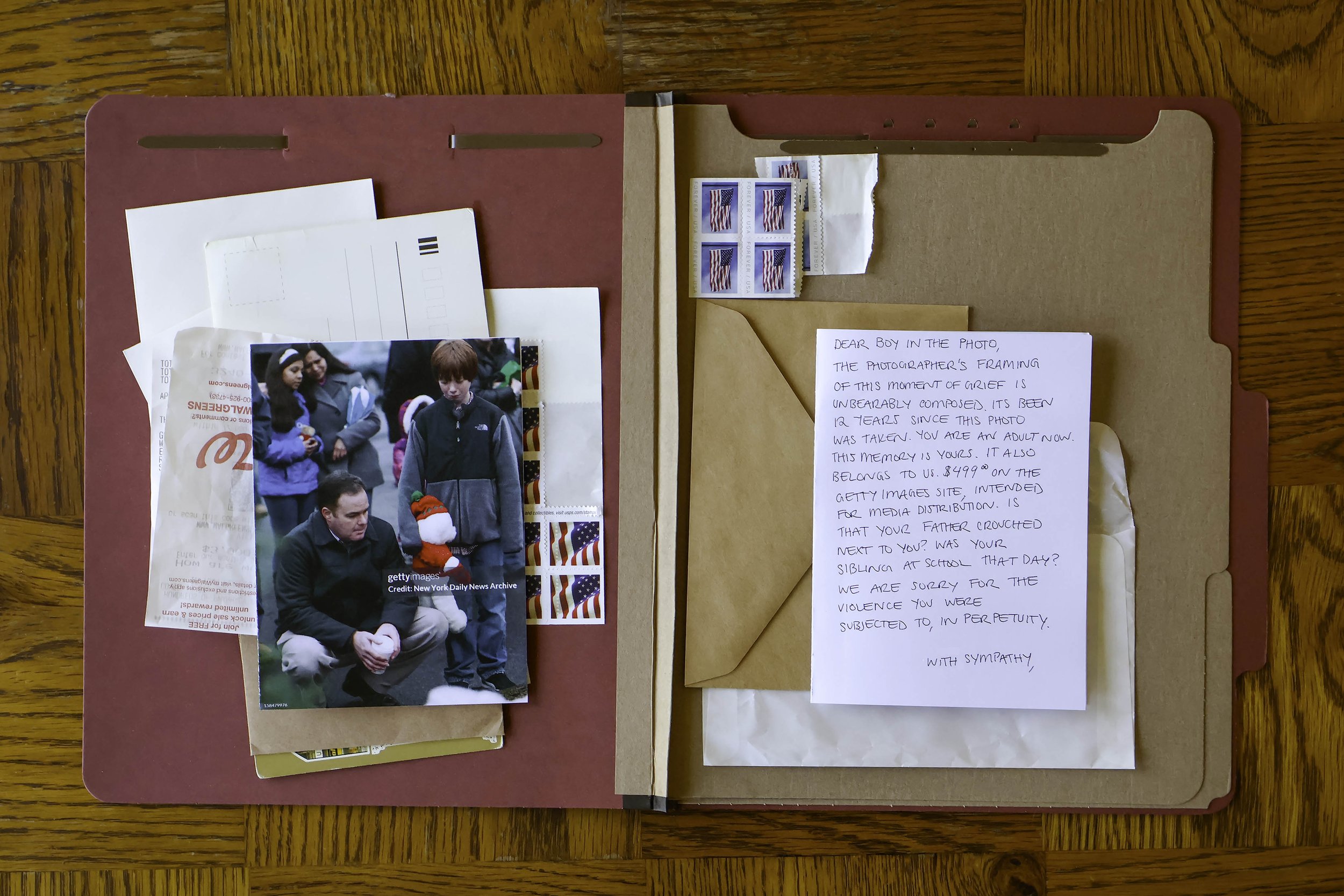

The commodification of condolences is further emphasized in the print titled well wishes, sympathies, utterances facing the opposing wall in conversation with sympathies for [Reserved for Name]. An open file shows a Getty Image of an adult crouched below an adolescent boy holding a stuffed animal, with two women in the background embracing, holding flowers. A solemn and sardonic letter is addressed to the boy, now 12 years older, offering this memory - for a price. American stamps, stationery, and a Walgreens receipt encircle the color-copied artifacts, illustrating a past event transformed into a curated narrative for public remembrance. The socio-cultural critique of capturing a moment—preserving a historical vestige that represents a specific type of memory, despite potential violations against the subjects depicted—serves as evidence of how mass media exploits emotional clickbait for memory-making. Similar to the Index receipt, the Getty image suggests an entry point into tragedy. Such as grief, the life of a memory can transform, fade, and resurface suddenly. While forgetting can lead to a sense of loss, focusing on memories can also amplify grief, as pain percolates in the absence of the loss. Therefore, loss is subjective, non-linear, and inherently interwoven with the collective experience. Jungian analyst James Hollis (1996) proposes that life both begins and ends with loss, and is continuously marked by various forms of loss, including the loss of connection, security, loved ones, bodily functions, ego identity, and unconsciousness. Becoming more conscious of loss involves engaging with memory, remembering, forgetting, suffering, meaning-making and imagination. This heightened consciousness requires being with oneself and hosting the wisdom of one’s episodic memory. In his seminal work Memory, History, and Forgetting, hermeneutic phenomenologist Paul Ricoeur (2004) elaborates on Aristotle's ideas, highlighting the significance of time. He notes that remembering happens after time has elapsed, with recollection emerging between the initial impression and its subsequent recall. Thus, time "remains the factor common to memory as passion and to recollection as action" (p.18). An Index of Americanisms encourages recollection as an active process, emphasizing not just the act of remembering but also an awareness of the value and measurement of time.

For the public, the allure of alleviating existential uncertainty temporarily is a compelling draw. Viewers might reflect on how society relies on and is overwhelmed by carefully created artifacts meant to express emotions or provide reassurance in responding in a controlled way. While mass media's formula of invoking a dissociative and emotionally one-dimensional portrayal of a crisis can offer temporary relief much like an anxiolytic medication, An Index in Americanisms reveals that this comfort is fleeting, leaving behind a persistent sense of unease. Can the simple act of participating—by actively taking a rose and engaging with the imaginative dimensions of conscious grief and pain—challenge the inherent positivistic limitations upheld by this type of indexing? What might arise from actively resisting monolithic narratives, vague lists, and sensationalized mourning? The compartmentalization of mental and emotional suffering through desensitization is subject to more careful examination, as widespread affective amnesia continues to fuel fear-driven fantasies. An Index of Americanisms is a reminder of the generative effects of returning to one’s imagination as both a respite and memory cultivator that fosters a kind of knowing that does not need proof of existence through logic and reason.

Dana Kline, PhD, September 2024.

———————————————————————-

List of References:

Bachelard, G. (2014). The Poetics of Space. Penguin Classics.

Cooks, B.R. &Watson, S. (2021). The Black Index. New York: Hunter College Art Galleries.

Fox, J. A., & Fridel, E. E. (2022). Keeping with tradition: Preference for the longstanding definition of mass shooting. Journal of Mass Violence Research, 1(2), 17-26.

Glissant, É. (1997). Poetics of Relation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Freud S. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916): On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works, p. 237-58

Freud, S. (1958). Remembering, repeating and working-through (Further recommendations on the technique of psycho-analysis II). In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 145–156). London: Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1914)

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-visioning psychology. Harper & Row.

Hollis, J. (1996). Swamplands of the Soul: New Life in Dismal Places. Inner City Books.

Krauss, R. (1977). Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America. Part 2. October, 4, 58–67.

Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Douglas, J. E. (1988). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives. Lexington Books.

Ricoeur, P. (2004). Memory, History, Forgetting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———————————————————————-

Images 1 and 2:

Installation shots at Winslow Garage, August 2024. Photo credit, Elizabeth Withstandley

Image 3:

well wishes,sympathies,utterances (Newtown) (2024)

Courtesy of the Artist.

Image 4:

sympathies for [Reserved for Name] (May 6, 2023), 2024

Courtesy of the Artist

———————————————————————-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is made possible by a grant from the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs.

Rachel Zaretsky is an artist and educator based in Los Angeles. She works with video, performance, installation, and photography to untangle the social space of memory and how it is reconstructed in public. She examines how systems of authority frame highly publicized tragedies that mold our collective memory. Central to Zaretsky’s practice is amassing and organizing materials as evidence. She sifts through commemorative detritus, which includes found imagery, archival material, and testimony, to understand what was forgotten and lost through active processes of remembering. She received her MFA in Art from the University of Southern California’s Roski School of Art and Design and her BFA in Visual and Critical Studies from the School of Visual Arts in New York. Her work has been exhibited at Human Resources, 18th Street Arts Center, and UTA Artist Space in Los Angeles; it has also been screened in New York and Germany.