“The Corrupted Archive” Riya Raagini on Luca Spano

‘The shadow has no feet,

No feet even as small as a rat’s

No feet with one in the past and one in the future’ – Masao

When Luca says that images come before reality, there is not a better manifestation to present his thesis than the cyberspace/infosphere (1) , the ‘mega-archive of the internet’ (2) . We are after all represented here by info graphics with a personal touch and Luca asks what remains when things begin to dwindle? What happens when an image falls apart? Do we fall apart?

The internet often makes users out of us, out of minimalists, coders, artists, co-creators, and co-performers, the ends don’t meet as peculiarly as one thread hanging past neatly at (just) two points. Across me (us) sit entities hosting worlds of their own, where I who is writing, am writing with, confirming with, and never making edits without, you – user, machine, the biosphere of the infosphere.

In a world (yet to exist) post-total-upload, where even the worst of our habits and most precious of totems have assimilated into the web, exists Luca Spano’s ‘The Corrupted Archive’, with a (corrupt) mind of its own. ‘Post total upload being a condition wherein we convert parts of ourselves into information and data…recording everything while waiting for a perfect digital copy ourselves to be created’ (3).

Luca refers to many kinds of corruptions which suggest contemplation, for a corruption in images, extends to the corrupted contents in our system of reality. When I say corruption, I mean an interference in signal, a microsecond delay that changes the entire lives and futures of pictures, swirling in the vortex of technological singularity (4) , in this arbitrary field of data, which we call the cyber-verse. Whilst entering their second, second life, these images remind oneself again, what do pictures want, now? (5) And in a reality where a loss of digital images/information is mourned its own share of grief, one is begged to ask what do corrupted images want?

When put together in Luca’s archive, these images resemble patchwork Kantha fabrics, frozen glacial memories – melting into the matrix of the archive, exposing hacks into their noise memory. Not once have images been considered less than things in Luca’s practice, ‘images are things’ (6) , and if things come with the limits of age and decay, images come with the limits of light, vision, and noise. With changing limits and structures does polishing really help anyone in a world where there is no rust, no oxidation? Digital polishing manifests itself in ways of the crisis brought about by the compulsions of a resolution-ary world. The task of the corrupted archive has been to bring together images which signal cracks in the systems of visual meaning-making.

In the economy of images resolution signals stability, the more the pixels the richer the picture is, deriving pleasure from the perceived, yet often falsified intermingling between clarity and resolution. In a world that is largely poor, the online (hesitantly?) reflects; among our digital footprint what we have gathered and watered digitization with, is largely the debris of poor images (7) (one can say we are uploading ourselves with the wrinkles, and all the back-aches). Talking about the archive Luca asks me to keep the poor image (8) in mind, and to treat him as an archaeologist digging into the depths of the internet looking for glitches, tracing anonymous alliances bonded by corrupt afterlives.

Corruption (unknowingly so) often kicks into an imaginary nostalgia, one that facilitates fictive imaginations to speculate, and when this turns into a cycle, narratives are held up high until someone hacks the archive; exposing the parallel worlds and history of digital glitches and blind spots, and mutations infiltrating the linearity of 2160p structures. Luca asks of the user, ‘It is a corrupted archive so please, corrupt the archive!’.

I do not consider Luca to be an archivist-artist here, but more of a receptacle-spectator engaged in the process of receiving and not reducting the archive, slacklining in the world of images at the verge of disappearance. The complex to save is not satisfied (as it is in the archive construed from a nostalgia towards a resurrection) while generating visual feelings with no clear purpose or ending point; being incomplete is deemed as an essential, for Luca ‘it is important to create conditions where you are missing something’.

Luca and I talked in length about the concepts of power in the construction and control of archives, and by extension in the making of history itself, establishing ‘statements as events’ (9) , and constructing narratives which then officially ‘belong’. These constructions establish a certainty that prevents the archive from being subjected to a two-way exchange, stitched deep into the locales on fixed timelines and categories, inscribing by formal means a formalized and inherent corruption.

Consequently, an intervention in the form of a counter-archive gives space for corruption to now express a sadness, a rejection, towards the caretakers of history and towards the stubbornness of perceptive reality and time. Such an exercise serves to intermingle the sense of informational certainty into uncertainty, ‘done into undone’ as Luca says, making space for an emotional forgetfulness, not very unlike how our own minds work in the wake of distortions one faces inside the archive of the conscious mind (10). But forgetting one thing often leads to remembering another, exposing the latent images inside pictures, ‘hiding their appearance and revealing their structure’ (much like what happens with shape memory alloys when they remember and recover their original size and shape upon heating), guiding digital memory closer to mental memory, for in a reality post-total upload we as humans / inforgs (11) might still forget, passerby faces, names, facts, and events as we do now.

I asked Luca if he has had a rather funny tryst with memory, has he ever forgotten the unforgettable? Luca pointed me to a time while living in New York, when he adopted a diaristic practice of making images on film, in order to find a more intuitive method for himself. From this practice, he gathered almost 140 film rolls (roughly more than 2000 images), but last year when he started developing these images, he didn’t remember taking many of them, ‘as though I’d lived another life simultaneously that I wasn’t made aware of’, says Luca, almost as if the informational flux of the digital and its remnants had leaked into Luca’s offline world, a reminder of the inherent lack pervasive of the contents of reality.

Ageing images, fall apart to expose their mnemic DNA, opening the passages to the funny thing that is memory, imploring if images and their inner contents also subscribe to Susskind’s holographic principle stating that information can neither be destroyed (nor created), leading to the question of where do they (images) find themselves when they forget, when they get corrupted?

Luca offers them such a site to gather, to enter their digital afterlife, where users still engage in the co-creation that is suggestive of the rise of pro-sumers (producer and consumer) of the digital age. In this afterlife, however, the idiosyncrasies of ordering and its remnants of linear hierarchies, of time, of categories, of genres, of language are done away with. The display of the archive is algorithmically randomized, traceable only through filenames so that each time a user engages with the archive, no memories of a structure are reinforced, a visual experience relational with the fluidity of everyday life, where likeness does not connote indistinguishability.

The archive for me also represents a site/ a memento mori for mourning digital grief, digital footprints which due to their nature of corruption are then fated to wander aimlessly, perhaps eternally in the cloud, never truly erased, yet never truly present in the way their origins might have purported, becoming digital ghosts in our second home, ‘hybrid and unearthly, hyper-present and eternal’ (12).

Luca asks me if the visual experience I take from the archive includes this feeling of in-between? This is what I was thinking too, that the images of the archive, are tied together not by their historical but their fleeting experience, like that of video stills, eluding all that is bothered by the stubbornness arising out of a scarcity of movement, ridding the images from the assertion to exert oneself, to prevent it from becoming something else, resulting in a visual experience place not here, and not being, but entirely elsewhere. This elsewhere I imagine must have something to do with the original digitization which brought them into the speed of ‘web time’, and post-corruption they have entered a colony of collapsing time, in an arbitrary field of data.

When I ask Luca about his experience of practicing artistic inquiry through the means of keeping a distance, and taking up the role of a receptacle-spectator, Luca says “These images often feel like holes, open wounds on a body interconnected with everything. I almost have the feeling I can look inside, like being on the crest of a volcano. You can look down into the crater and see the lava, but the temperature is so hot, the smokes and vapor are so strong, that you can't really have a clear image of the burning magma. You get a glimpse of it, a guess. Maybe it is more emotional than informative, maybe the information is in the emotions, the incompleteness, the ungraspable things they contain.”

Renee Green echoes a very similar sentiment when she talked about her archival art practice, “a strain which recurs in my work has involved the probing of in-between spaces, which can appear to be holes, aporias, absences. For example, between what is said and what can be comprehended…what is seen and what is believed; between what is heard and what is felt’ (13).

Both Luca’s and Renee’s sentiments point toward a historical impulse challenged by the lack of structured remains, no longer representing a thread of continuity, but a fracture, the mark of which is amnesia, constructing a dream-like place, where visual research happens by the chance encounter of distortions and poesis. W. J. T. Mitchel (I imagine sighs) says, that it is through the loss of poesis that images become performative (14). Luca exercises the archival impulse which seeks to prevent the disappearance of images, to prevent inner structures and visuality of informational and digital loss from disappearing, in a gesture of retrieving alternate knowledge, ‘concerned less with absolute origins and more with obscure traces’ (15).

Obscurity too comes with its own set of parameters in the process of residing in a place of fluid meaning-making exercises in ‘The Corrupted Archive’. As a matter of visual research, it comes grounded with these labels (to reiterate that in spite of being corrupted, it is an archive), while still ‘considering the error as a space of decisional autonomy of a machine-based nature’ (16). There is the randomized eight-letter title as an ode to the average password length on the web (giving away the security of the insides of an image), we have been told which media it is, the provenance, nature of corruption, pattern, predominant colour, and predominate shape, and all the contents are freely available for download.

By placing a new set of parameters to identify the contents of the archive, Luca provides us with the glimpse of a future wherein digital loss, or the perception of one, can bring one to mourn, and it is not as if we are not almost in said future.

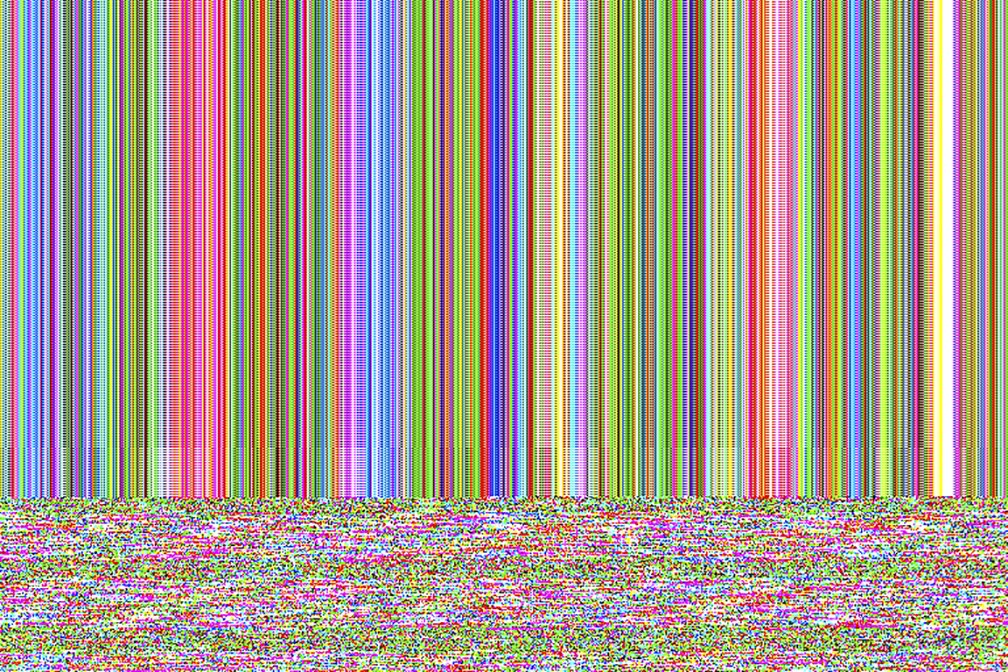

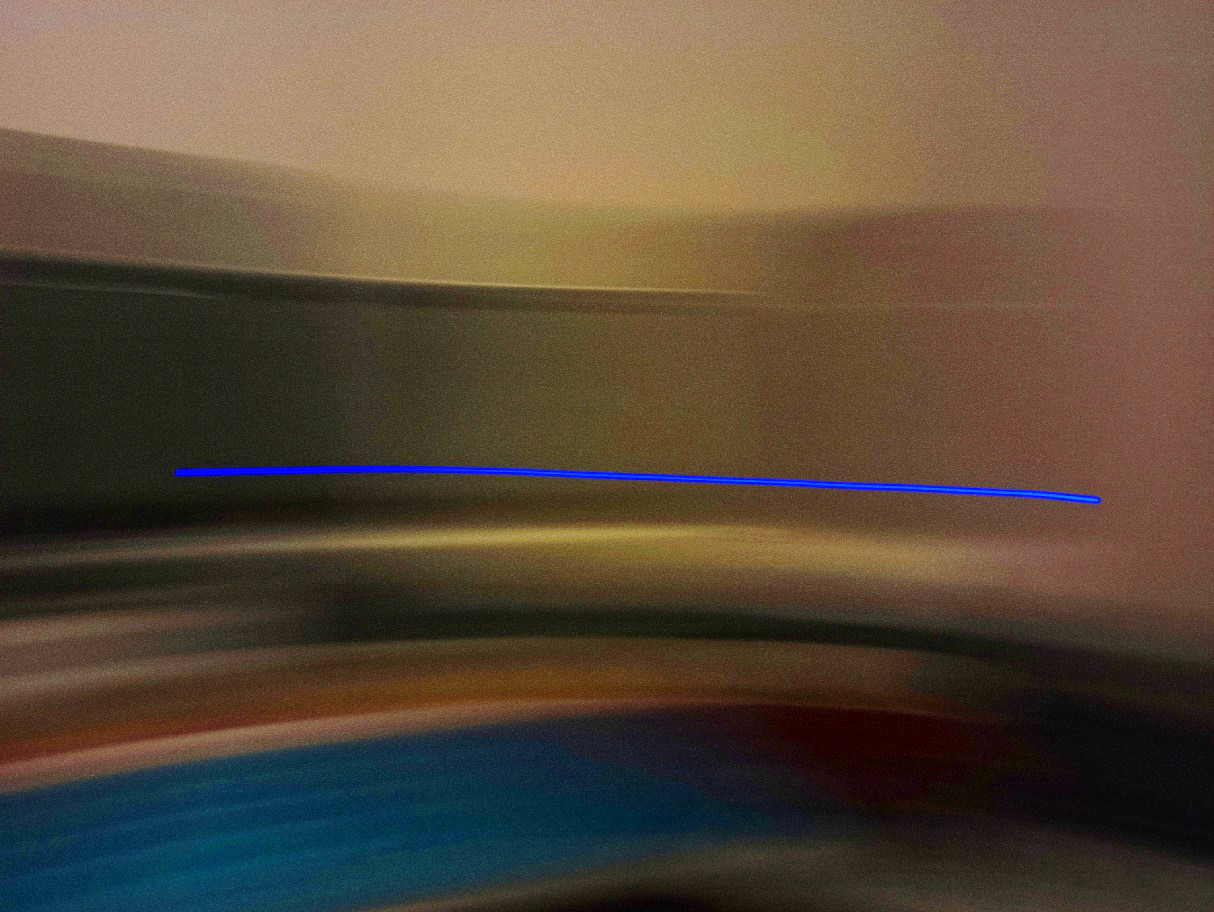

By way of participation, Luca’s archive is communicating with the future while continuing to learn and evolve, one gaze of the image looks backward, while the other looks forward. I too participated in the archive as part of ‘Bariya’. What participating, and being asked to re-interpret some of the images helped me with, was to come to realize that each corrupt sense action differs in its signature from the other, and in its digital manifestation it is as if it leaves its own heat signature – an ultraviolet poesis. Each image still retains its differentiation, as if each vase breaks in a different way, and how must the shadows of each vase dismantle differently too. (Figures 1,2, and 3 are images from the archive, and 1(a), 2(a), and 3(a) are re-interpretations, Figure 4 is a digital selfie with the archive.)

In all this - in the putting together, then dismantling, in introducing a non-hierarchical order of things in cycles of corruption which get denser by the day, Luca says that he seeks to put the archive upside down, hanging by its legs, so that and we can be witness to the matrix disappearing and the results – the interactions and interventions become the matrix, risking as a receptacle here an ever shuffling headache for himself, while opening the possibility for users to transform the archive as they please. Artists are called upon to re-interpret the archive’s contents, and the users are called to participate by submitting their corrupted files, and together this archive stays alive. The seeds have been sown, the clouds are here, and someone has their eyes on the soil, and there are some of us who are wishing for an inventive bloom, the rest is left for the cyber verse to decide.

(Luca Spano’s ‘The Corrupted Archive’ is an archive of corrupted images, focusing on the point where the digital file collapses, altering its structure and perceived presence. The project is accessible in the form of a website, which allows the user to browse, download, and use any content for free. The users can also participate by submitting their own corrupt images. This material is a resource for artists to interact with and re-interpret)

Developed by Maurizio Lai, and supported by Prospect Art, ‘The Corrupted Archive’ can be engaged with here - https://corruptedarchive.com

Figure 4: Digital Selfie with the archive

Figure 1

Figure 1(a)

Figure 2

Figure 2(a)

Figure 3

Figure 3 (a)

(1) Luciano Floridi’s concept of ‘infosphere’ stating that just as the biosphere concerns what is alive, the infosphere concerns with what interacts.

(2) Hal Foster, An Archival Impulse, Vol. 110, Autumn, 2004, The MIT Press

(3) Davide Sisto, ‘Online Afterlives: Immortality, Memory, and Grief in Digital Culture’, Translated by Bonnie McClellan-Broussard, September 2020, 31.

(4) Kevin Kelly, editor and co-founder of Wired magazine, describes the technological singularity as that fateful moment in history when the changes that have happened over millions of years will be superseded by the change that will take place in the next five minutes.

(5) Referring to W J T Mitchell, ‘What do pictures want? The Lives and Loves of Images’, 2004, The University of Chicago Press

(6) In conversation with Luca Spano

(7) Hito Steyerl, ‘In defence of the Poor Image’, Issue #10, November 2009, E-flux Journal

(9) “We are now dealing with a complex volume, in which heterogeneous regions are differentiated or deployed, in accordance with specific rules and practices that cannot be superposed. Instead of seeing, on the great mythical book of history, lines of words that translate in visible characters thoughts that were formed in some other time and place, we have, in the density of discursive, systems that establish statements as events (with their own conditions and domains of appearance) and things (with their own possibility and field of use). They are all these systems of statements (whether events or things) that I propose to call archive.” – Michel Foucault, ‘The Archeology of knowledge: And the Discourse on Language’, 1982, Vintage, 126-31.

(10) Sigmund Freud, ‘A Note upon the Mystic Writing Pad’, in Ed. Charles Merewether, ‘Documents of Contemporary Art: The Archive’, 2006, Whitechapel and The MIT Press

(11) “Informational organisms, mutually connected and embedded in an informational environment (the infosphere), which we share with other informational agents, both natural and artificial, that also process information logically and autonomously.” – Luciano Floridi, ‘The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality’, 2014, OUP Oxford, 94.

(12) Davide Sisto, ‘Online Afterlives: Immortality, Memory, and Grief in Digital Culture’, Translated by Bonnie McClellan-Broussard, September 2020,

(13) Renee Green, ‘Survival: Ruminations on Archival Lacunae’, in in Ed. Charles Merewether, ‘Documents of Contemporary Art: The Archive’, 2006, Whitechapel and The MIT Press

(14) Helena Schmidt, ‘What is the Poor Image Rich in?’, in ‘Post-Digital, Post-Internet Art and Education’, June 2021, 203-221.

(15) Hal Foster, An Archival Impulse, Vol. 110, Autumn, 2004, The MIT Press

(16) Luca Spano, ‘The Corrupted Archive’

Luca Spano is a multidisciplinary Italian artist. His research focuses on the components of the image’s architecture, exploring their behaviors, uses and materiality in relation to the socio-anthropological dynamics of our society. Within this framework, recurring topics of his work are representation, knowledge construction and colonialism. His practice moves between photo-based works, installations and sculptural artifacts.